And then came a moment, no more than a hair’s-breadth of time, I fell in love.

No, not what you think. This was a different love, true love, an affair of the heart. It happened suddenly, totally unexpected, following five straight days of rain.

I was in Hoi An, in central Vietnam, where rain is not a stranger. Nor typhoons, and this one had swept west from the Philippines, sideswiping the coastal middle of this long, skinny country before plunging south to cause untold deaths and damage.

For the ten days prior the weather had been gorgeous. I was staying at an old hotel sitting directly on the river, and until the rain began the place had proved a terrific choice. For whatever lack of mod-con comfort I may have sacrificed was more than compensated by its position smack in the middle of things Vietnamese: the morning market, the old town with its wonderful architecture, the bustle I thrived on in this part of the world.

Too, I’d now been here long enough that the standard come-on cries of "Whereyoufrom?" and "Sircomelookingmyshop!" had slackened off, replaced by frequent smiles of recognition and now-and-then good-natured calls of "Hey Santa Claus!" and "You Fidel Castro!" People pointed out the old whitey with grey beard to their toddlers, who grinned and waved. Tough looking teenage kids on motorbikes would soften and return nods when I stopped my bicycle next to them at red lights.

Also during these ten days I’d encountered my prime purpose for returning to Hoi An. A decade before, I had met a family, the living cliché of people who will give you everything despite having nothing. They knew hardly any English and my pronunciation of Vietnamese was – still is -- hopeless, yet one way or another we spoke volumes, especially the mother of this family and I.

When I learned the youngest of her four children, then age eleven, would have to leave school because the family hadn’t the money to send him further, I volunteered to finance the remainder of the boy’s education. So for the past ten years I’ve been sending an annual amount so miniscule in Western terms it barely exceeds my local bank’s fee for international swift code transfer.

During this time I have on untold occasions promised myself a return visit to my Hoi An family, yet every year my annual Asian travels seemed to take me elsewhere. Even this past year I’d already booked for India when suddenly the Universe picked me up by the scruff of the neck, shook some sense into my procrastinating brain, then finger-flicked me in this direction.

Over the past few years I had received the odd email, in pretty bad English, from young Minh. It was the kind of correspondence that more than hinted of acquiescence to a mother’s demands. He sounded genuinely happy, though, when I emailed him last September to expect me in October, but when I got sidetracked in Cambodia and didn’t make it till late November, he’d already left for Hanoi, where he was enrolled in language classes. From Hoi An I wrote, Couldn’t you return home for a brief time? And Minh wrote, Come to Hanoi and I’ll show you around the city! Stalemate.

In truth, I didn’t care to take on Vietnam’s fast-paced capital; at the same time I was loath for him to interrupt his studies just to accommodate me. The situation was resolved one evening while visiting Minh’s sister. When I explained my dilemma, she calmly got on her mobile, rang his mobile, and following a brief conversation that seemed to entail neither coaxing nor guilt-tripping, she reported: "He’ll fly home tomorrow."

Minh was nearly as tall as me, had long hair and wore glasses, behind which were eyes that appeared to see much more than might be expected of a 21 year old who until recently had rarely ventured out of this provincial town. Even more surprising, his spoken English, unlike his written, was close to fluent. In those first few minutes I sensed that he was thoughtful, cynical, hopeful, questioning, overly self-critical. Hell, I thought: he could be my spiritual clone!

We spent the better part of a week together. He owned, I discovered, no less than five ancient Vespas. He would buy the motorbikes cheap, then customize them to his liking. His sister told me he had been offered huge sums for them, both by locals and foreigners. He refused to sell. "They’re my passion. I’d rather work a mindless job to get money than part with my Vespas."

Another shared trait: bloody pig-headedness.

Me on back of his favorite bike, we tooled all over the district. He took me through areas very few visitors to Hoi An ever got to see. And we talked. About everything. What he wanted to do, he said, was open a vegan restaurant in Hanoi, which he would use as a base for running eco-tourism trips for foreigners interested in vegetarianism, meditation, visiting family-run organic farms in the countryside. "I want people to experience the real Vietnam," was the way he put it.

It all sounded good. What I didn’t know, still don’t, was this: is he a dreamer or a doer? A talker or a walker. If I handed him a bunch of money, would he get together such a meaningful venture, or amass the world’s largest fleet of revamped old Vespas?

Every afternoon we’d ride to the beach, five km away, and walk the sands in silence. Once we came upon a dozen locals struggling to maneuver an old wooden fishing boat up the dunes to higher ground. We pitched in, and the extra muscle did the trick. All the while, the locals couldn’t take their eyes off the bald, longhaired and bearded gringo, laughing and chattering away.

"What were they saying?" I wondered when we’d moved off. He was quiet some moments, then: "They said you looked like Saddam Hussein." He shook his head. "Saddam Hussein! And they think he’s still president of Iraq! You see why I’m happy to be out of here and living in Hanoi?"

All along, the weather had been great. Ironically, the day Minh flew back to Hanoi was when the rains began. Rain when I’m on the road is never a happy situation. Five days straight? My spartan hotel room became a prison cell: dingy, clammy, closing in on me. Lichen was forming on the walls of my brain. Add to this the constant power failures endemic to Southeast Asia, plus the hotel’s lack of a generator…

Everything was getting to me. The tourists: young Euros, all armed with the Idiot’s Guide to Avoiding Thinking and Making Decisions for Yourself, aka Lonely Planet. Old Euros, overweight, overcautious and over here, crammed into tour buses which retched them out for 90 seconds max at "significant starred sites". And the new breed, wealthy South Koreans and Mainland Chinese, always in battalions marching in lock step, digitally snapping one another standing stoic-pussed in front of, ah, yes, "significant starred sites".

Normally, I never see them; they do not exist in my traveller’s vision.. Five days of rain and they were constantly in my view, crawling through my head. But irking as they were, these automaton beings were not nearly so irritating as the locals. I listed my moans: The Vietnamese giggled like children, they walked like snails on Prozac, piloted whatever their vehicles, motorbikes mostly, but as well anything from single-speed bicycles to the ancient Russian trucks with ear-bashing two-stroke motors, like total maniacs. Worst of all, though, everything, every blessed thing, you wanted to buy, you had to bargain, bargain, bargain. And then got screwed.

I went to purchase aspirin for a worsening headache at one of the numerous tiny pharmacy stands. As usual, I was ignored while locals who came up after me were being served. Finally I pushed my way directly up to the woman on the other side of the counter.

"Yo, am I invisible?" I yelled. "Here I a-a-a-am! Hello-o-o-o!!"

She tossed a box of aspirin on the counter without eyeing me. I thumbed it open and took out a strip of ten sealed tablets.

"Twenty thousand dong," she said, still not looking my way. US$1.25.

Loud: "Holy hell, am I in Hoi An or New York?" Even louder: "What, I have a long nose and white skin, I pay four times as much as him?" – nodding at the Vietnamese standing alongside. "You’re supposed to be a professional, not some old woman selling t-shirts in the market!" Still not facing me, she took from the carton another strip of ten.

"Two for 30,000 dong."

The following day, I was cycling along a narrow street. A huge tour bus turned in just behind me and began bearing down, the driver leaning on a horn that would waken fossilized dinosaurs. Since the bus took up the entire breadth of the street, there was nowhere for me to pull over unless I jumped the high curb. When I pedalled faster, the driver sped up, the bus less than a meter behind, horn blaring deafeningly.

I stopped. Behind me, the driver slammed on the brakes. Straddling the bike, I twisted around in slow motion, glared for several moments. Gave a classic De Niro snarl. Bellowed: "ARE YOU HONKING AT ME!!?"

I definitely was losing it.

Day five of the downpour, the river finally breached its concrete bank, began racing up the streets. Hoi An people expect this; it happens a dozen times a year. Just another day at the office. Bicycles and motorbikes plowed through the water, now reaching to nearly seat level, competing for navigable space there with small boats. Even when the rain stopped on day six, the river, fed now by waters flowing down from nearby mountains, continued to push further through the town.

"I’m going to Hanoi," I announced somewhat frantically the following morning to a Vietnamese friend. "Or Bangkok. Anywhere. I have to get out of here."

"You want to go to a big, dirty, loud city?" she cried. "You told me you don’t like big cities."

"Yes, but --"

"You just need to get out of that hotel. I don’t know why you stay there anyway." She grabbed my wrist. "You come!"

She sat me on the back of her motorbike and took off. I had no idea where we were headed. Five minutes later she pulled up to a somewhat flash hotel. Inside, she sought out the owner, a woman. "This my sister," she informed me. I knew she had no sister, but in Vietnam the term could mean anything from good friend to sixty-fourth cousin. Much blah-blah between them. Then to me: "We look at room."

"But --"

She dragged me up the stairs, showed me a well-appointed room with a tiny balcony that looked out onto a large, tree-lined field of morning glory currently being harvested by a few old people wearing the standard non conical straw hats and shoulder-toting the ever-present quan ganh, yoked twin baskets. In the background I could see a magnificent white heron. The whole image was a postcard.

"You like?"

"Well, yes, except a room like this must cost a small –"

"Come!"

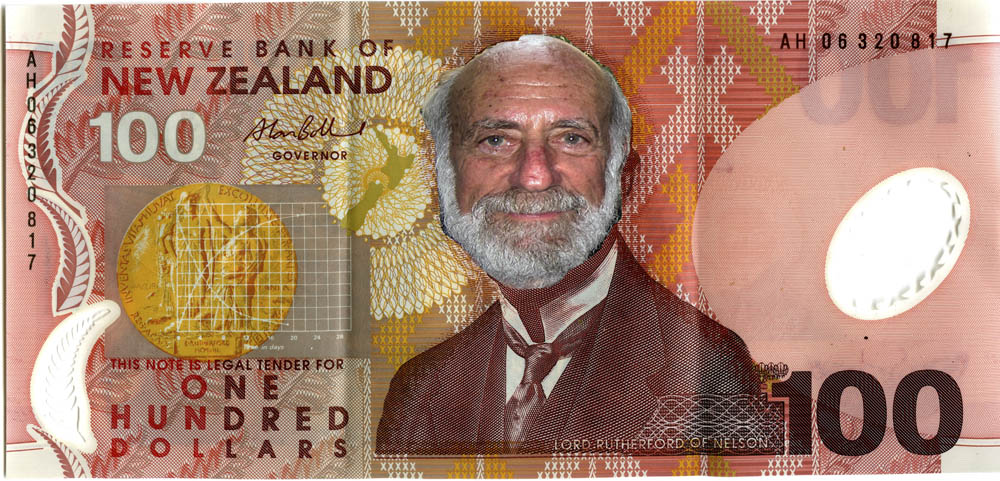

Back downstairs, more blah-blah between the "sisters", followed by a rapid transfer of banknotes bearing the likeness of Ho Chi Minh.

"Ten days paid," my friend informed me. "Right up to when you fly home."

"Wait a minute! You can’t, I mean, I won’t let you --"

She moved closer, stood on her toes until her face was right next to mine. "Why not? You pay ten years Minh’s schooling. You even pay his airfare here and back to Hanoi. Yes? You do this?" There are no secrets in a small Vietnamese town, none. "Now payback time!" And she left me standing slack-jawed, mounted her Honda and tooled off.

But this is not what caused me to fall in love. That happened later in the day.

The new, ever-so-comfortable hotel room plus the clearing sky did indeed lift the pall that had been hanging over me. I went for a long bicycle ride. Felt great. There might’ve been a robotic tourist or two, maybe even a few giggling, slow-walking, insane drivers bargain-bargain-bargaining on the streets where I pedalled; I just didn’t see them.

That evening I had dinner with an American friend living in Hoi An. When we finished, she suggested we walk down and take a look at the burgeoning river. We didn’t have far to go. Half a dozen small, old wooden boats now sat upon water 500 meters from the river’s normal boundary, each bearing an ancient crone beckoning us with the standard fingers-down hand wave to hop in and go for a nocturnal cruise. Around us on both sides of the skinny street it was business as usual: the myriad plagiarized photocopied-book shops, pirated DVD shops, counterfeit The North Face bag shops, bogus official NBA shoe shops. As well as restaurants offering the same-same rice and noodles meals, plus pushcart vendors hawking everything from soggy popcorn to sickly-sweet, sickeningly colored soft drinks. And everywhere on the narrow footpaths people, as they do here, squatting on their haunches, bless their knees.

The sights, the sounds, the smells wove a web around me. Of a moment I was filled with a strange sensation, like a thousand fizzy bubbles forming in my gut and spreading rapidly throughout. My friend then pointed behind me, up toward the rooftops. I turned to look. The moon. Full. Peeking out from behind a cloud. Laughing down on all of this.

And that’s when it happened.

There are a handful of places in the world I have special, ongoing love affairs with: Luang Prabang…Pushkar…Nyaung Shwe…Suzhou…Ohope.

Add one more. Because at that moment, I fell tits over toes in love with Hoi An.